I have been here in Korea for just over two weeks and am settling in at Camp Red Cloud, located north of Seoul. I think I’ve done a poor job in the blog of laying out the last month and half in which there has obviously been some significant changes in what I am doing.

I have been here in Korea for just over two weeks and am settling in at Camp Red Cloud, located north of Seoul. I think I’ve done a poor job in the blog of laying out the last month and half in which there has obviously been some significant changes in what I am doing.

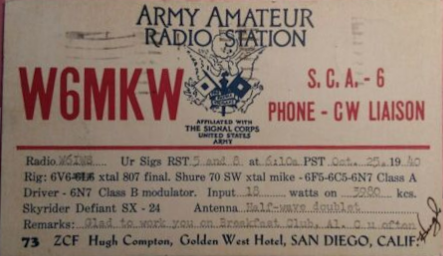

On May 20th, I graduated from the School of Advanced Military Studies, culminating my two years at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, knee deep in graduate-level text books and Army field manuals. One of the requirements for graduation was to write a monograph on a military subject. I choose to write on the early history of MARS prior to World War II, when it was known as the Army Amateur Radio System (AARS). During this years Hamvention at Dayton, I had the opportunity to present the paper and I am pretty happy on how it all came together. No significant research had ever been done on early MARS history so I spent the majority of my research combing through primary sources and even conducting a few interviews with the few remaining former members of the AARS. If you have an interest in MARS, the history of radio in the Army, or the origins and organization of radio emergency communications, the paper is available here at no cost. One facet to the history of the AARS that I found intriguing was the relationship that grew between the AARS and the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression. The ARRL recently posted a short article I wrote on the subject and you can see it here if you are interested.

My assignment following school was to Korea with the 2nd Infantry Division. To actually get there, I elected to take a less typical means of transportation for part of the journey. I decided to take Amtrak from Kansas City to Seattle, where I would board a government contract flight to Seoul. I had ridden trains quite a bit in Europe, but never had taken a train for more than a short distance in the United States. I had also recently read Waiting on a Train: The Embattled Future of Passenger Rail Service, A Year Spent Riding Across America by James McCommons. If you are interested in passenger rail travel, enjoy a good road trip, or would like to know why train travel fell victim to the car culture, you will enjoy this book. The author, James McCommons, travels all the primary Amtrak routes (with mixed experiences) and talks with US rail movers and shakers around the country. Overall, he said Amtrak was good and getting better. I decided to see for myself.

One of the countries more historic and picturesque routes is that travelled by the California Zephyr. Originating in Chicago, the train traces its way west, climbing through the Rockies west of Denver and on to the Sierra Nevada’s an into California, terminating near San Francisco. My folks still live where I grew up near San Jose, so California was great for a stop over. I could then take Amtrak’s Coast Starlight from San Jose through Northern California, central Oregon through Eugene and Portland, then on to Seattle.

The train ride west was wonderful and I did write a post about it. The stop over in California was a lot of fun. Arriving during the early evening of Thursday, June 10th, I was able to get some sleep and meet my dad for some QRP portable field operations. We headed up to the Santa Cruz Mountains, above Saratoga, strung up a 40m dipole and had fun playing with my FT-817 and KX1. Although we didn’t achieve any great DX contacts, it was a great time. Saturday morning we headed over to a local monthly hamfest known as the Electronics Flea Market @ De Anza College. De Anza College is a little known junior college which has overseen the growth of Silicon Valley. Although I did not find anything I couldn’t live without, I enjoyed roaming around and seeing what the vendors had.

Before lunch, we headed over to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View. Founded in 1999, the museum opened long after I had left the Bay Area. Very cool museum!

Then it was back to the train station in San Jose and I hopped on the Coast Starlight and headed north. The train ride was relaxing with some amazing scenery.

I spent Sunday night in Seattle and caught a shuttle bus on Monday to SEATAC. Flying with AMC can be an experience and differs from a commercial flight. The AMC counter was located at the far end of the international terminal and I joined a long line of guys with short haircuts and heavy, canvas green bags. Although I had to check in at 7:00pm, the flight wasn’t scheduled to board until 1am. They didn’t pack the flight, so there was a little elbow room. Instead of flying directly to Korea, our route would take us to Anchorage, followed by Yakota (near Tokyo) and then Osan Airbase in Korea. We got to Anchorage, deplaned for fueling, reboarded and then sat for three hours. Apparently the weather was bad over Japan, so we were held over for about 24 hours in Anchorage. I had been stationed in Alaska during 1993-1994 and it was nice to see that midnight sun again (sunset at 11:30pm with sunrise at 4:30am).

From Anchorage to Japan with a short layover and then on to Korea. The rest of the story is here.

And on the amateur radio side of things… My equipment is here. I shipped over my Icom IC-7000 for HF and a Kenwood TM-D710A to use with my EchoIRLP node. Also on the way is a Davis Vantage Vue weather station that I hope to get on line and on APRS. I need to get my Korean license and have all the necessary paperwork. Just need to get it turned in now. There is a monthly hamfest in Seoul next Sunday that I am going to try an attend – that should be an experience and I will have to bring my camera.

Have you been enjoying Jeff’s new podcast at KE9V.net? Cornbread Road is a Jeff at his best, weaving a tale of mystery and amateur radio in the heartland.

I will endeavor to keep my blog up to date with posts about my experiences here in Korea.

I am closing in on the end of my research concerning the history of MARS, focusing on the early years when the organization was known as the Army Amateur Radio System (AARS). I choose this as a research topic because no one has ever written a thorough history of MARS.

I am closing in on the end of my research concerning the history of MARS, focusing on the early years when the organization was known as the Army Amateur Radio System (AARS). I choose this as a research topic because no one has ever written a thorough history of MARS.

I’m continuing my research of

I’m continuing my research of  I contacted Dr. Haring (she’s a professor at Auburn University) and asked if she could provide me any additional information on the MARS Bulletin. Dr. Haring told me that she had accessed the MARS Bulletin while conducting research at both the Library of Congress and Columbia University’s library. She also recommended a search tool called

I contacted Dr. Haring (she’s a professor at Auburn University) and asked if she could provide me any additional information on the MARS Bulletin. Dr. Haring told me that she had accessed the MARS Bulletin while conducting research at both the Library of Congress and Columbia University’s library. She also recommended a search tool called

– Following another lead for QST, I found a letter to the editor in the October 1998 issue from a gentleman by the name of Robert Gabardy, K4TJ. In the letter, Mr. Gabardy explained how he was part of a team which formed to bring MARS back to life back in 1949 and explained how they arrived a the new name for the organization. I was able to contact the retired Lieutenant Colonel Robert Gabardy, who served in the US Army for a period of over 23 years and is a veteran of WWII. He was able to give me a bit more background and also agreed to respond to some additional questions that I am developing.

– Following another lead for QST, I found a letter to the editor in the October 1998 issue from a gentleman by the name of Robert Gabardy, K4TJ. In the letter, Mr. Gabardy explained how he was part of a team which formed to bring MARS back to life back in 1949 and explained how they arrived a the new name for the organization. I was able to contact the retired Lieutenant Colonel Robert Gabardy, who served in the US Army for a period of over 23 years and is a veteran of WWII. He was able to give me a bit more background and also agreed to respond to some additional questions that I am developing. – My last hot lead comes from another QST letter to the editor from the June 1998 issue that had caused LTC Gabardy to write in. This letter was from George Hart, W1NJM, a former staff member of ARRL… but also a former member of the AARS and also an Army veteran of WWII. From what I can tell now, Mr. Hart is in a retirement facility in Connecticut. I am going to try to reach him tomorrow and see if I can conduct a telephone interview with him. He would be an amazing source of information into how AARS functioned. I am particular interested in trying to determine why the US Army failed to directly draw from the pool of trained AARS operators to fill the ranks of the Signal Corps after Pearl Harbor. Equally confusing is why the Army didn’t maintain the organization to continue to fulfill its domestic responsibilities of acting as an auxiliary communications network. Instead AARS disintegrated within hours after Pearl Harbor, but only to be replaced later by the Wartime Emergency Radio Service (WERS).

– My last hot lead comes from another QST letter to the editor from the June 1998 issue that had caused LTC Gabardy to write in. This letter was from George Hart, W1NJM, a former staff member of ARRL… but also a former member of the AARS and also an Army veteran of WWII. From what I can tell now, Mr. Hart is in a retirement facility in Connecticut. I am going to try to reach him tomorrow and see if I can conduct a telephone interview with him. He would be an amazing source of information into how AARS functioned. I am particular interested in trying to determine why the US Army failed to directly draw from the pool of trained AARS operators to fill the ranks of the Signal Corps after Pearl Harbor. Equally confusing is why the Army didn’t maintain the organization to continue to fulfill its domestic responsibilities of acting as an auxiliary communications network. Instead AARS disintegrated within hours after Pearl Harbor, but only to be replaced later by the Wartime Emergency Radio Service (WERS).

It has been a tough few weeks with multiple papers and writing assignments falling within a very small period of time. I kept my nose to the grind stone and with the hep of the XYL running interference to keep me away from distractions (amateur radio being one), I successfully finished all my work!

It has been a tough few weeks with multiple papers and writing assignments falling within a very small period of time. I kept my nose to the grind stone and with the hep of the XYL running interference to keep me away from distractions (amateur radio being one), I successfully finished all my work!  Since July I have been attending the

Since July I have been attending the